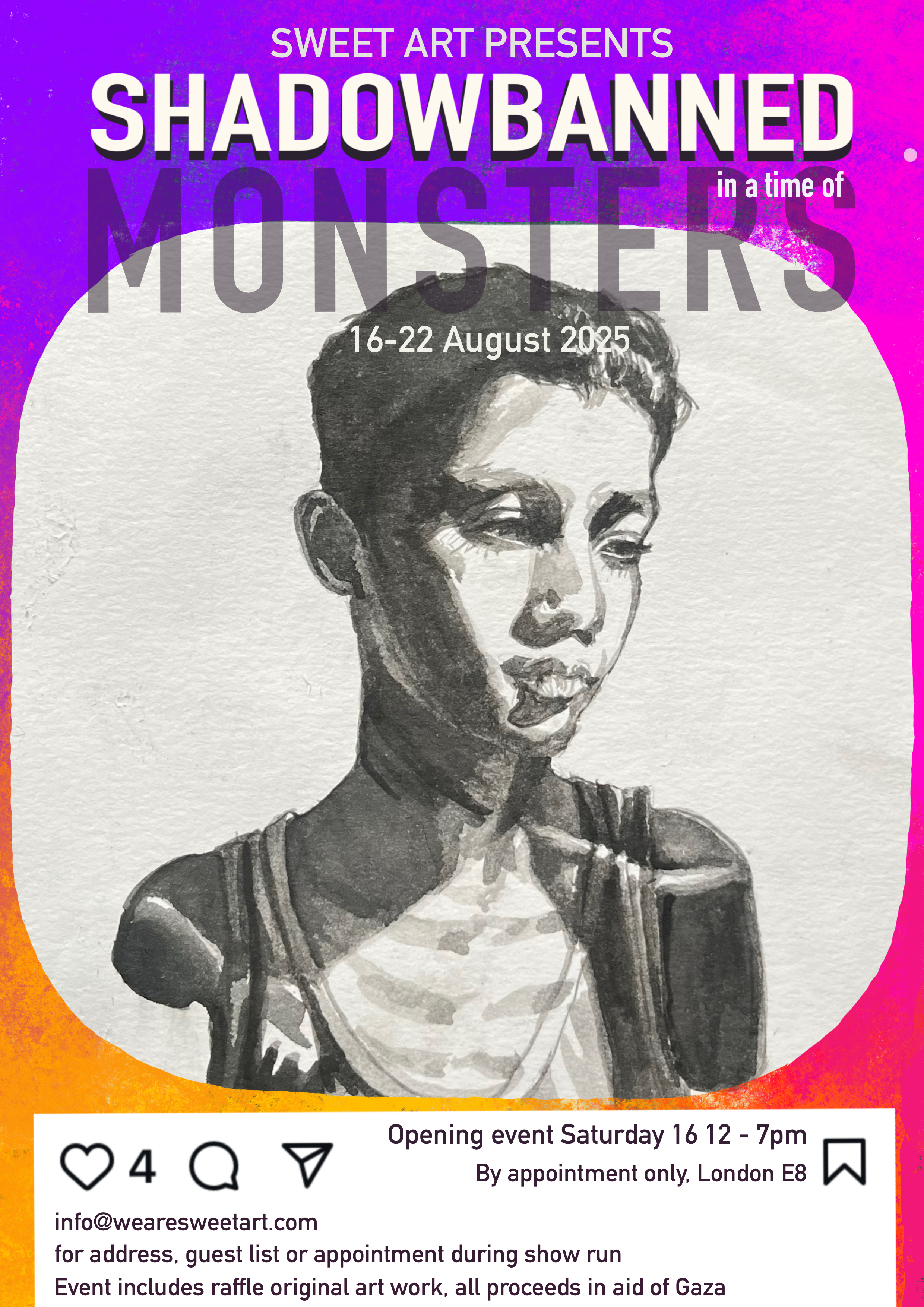

SHADOW-BANNED IN A TIME OF MONSTERS

Shadow-Banned in a Time of Monsters

Renata Fernández

Art Bypass Gallery, London | 16–22 August 2025

Renata Fernández’s exhibition Shadow-Banned in a Time of Monsters offers a deeply affecting meditation on the politics of visibility, the brutality of contemporary humanitarian crises, and the quiet persistence of care. Across drawing, painting and installation, the Venezuelan-born artist explores how violent imagery—especially those documenting the genocide in Gaza—circulate, disappear, and haunt our digital and emotional landscapes.

The exhibition takes its title from Antonio Gramsci’s observation: “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.” For Fernández, this phrase captures the moral collapse of our current moment—a time when atrocity is both hyper-visible and algorithmically obscured.

At the centre of the exhibition is My Social Media Feed in Ink (2021–ongoing), an expansive series of over 200 ink drawings meticulously based on images drawn from the artist’s own social media feed. These small, square works—initially begun during the pandemic—slowly transform fleeting digital ephemera into hand-rendered witness. The series makes grief tactile and unscrollable. In their intimacy and repetition, they become a form of resistance: against erasure, against numbness, against the false neutrality of the algorithm.

In dialogue with the drawings is a new large-scale work, Artist-Made Shelter for a Man-Made Tragedy Such as Genocide. Part painting, part imagined refuge, the piece constructs a symbolic shelter inside the gallery—a fragile, futile act of protection assembled from images, found objects, and memories. It doesn’t pretend to shield against real-world violence, but instead offers space for reflection, for mourning, and for honouring survival. This shelter suggests that even amid devastation, beauty and dignity persist.

Throughout, Fernández asks: What role can art play when the world is on fire? If it cannot protect, can it at least bear witness? Offer shelter? Sustain memory? Her answer is a resolute yes.

In refusing to look away, Shadow-Banned in a Time of Monsters asserts the power of art not as spectacle or solution, but as a site of conscience—where grief can be held, and where solidarity, however fragile, might still take root.

Georgia Taylor Aguilar, Curator, ACAVA

Content Warning

This exhibition contains artworks and themes that address war, genocide, grief, and visual representations of violence, including depictions of harm to children. Some material may be distressing. Viewer discretion is advised.

PRESS RELEASE

Shadow-Banned in a Time of Monsters: A Solo Exhibition by Renata Fernández

Art Bypass Gallery (We Are Sweet Art), Dalston, London | 16–22 August 2025

Opening Event: Saturday, 16 August 2025 | All-day fundraiser for Doctors Worldwide supporting their Gaza relief efforts

Venezuelan-born artist Renata Fernández presents Shadow-Banned in a Time of Monsters, a poignant solo exhibition exploring themes of censorship, resistance, and resilience in the face of genocide. Hosted by Art Bypass Gallery—an artist-run feminist initiative amplifying marginalised voices—the show challenges conventional art norms while raising urgent humanitarian awareness.

The Exhibition

The title draws from Antonio Gramsci’s famous phrase, "Now is the time of monsters," reflecting societal upheaval where old orders crumble and unsettling new forces emerge. For Fernández, this "time of monsters" mirrors the digital and physical repression faced by those bearing witness to Gaza’s devastation.

The exhibition features two central works:

"My Social Media Feed in Ink" (2021–ongoing): Over 200 small ink drawings appropriating images from social media, started during the pandemic’s isolation and escalating into a harrowing archive of Gaza’s genocide. Recognisable to many, these images confront the algorithmic suppression of shared outrage.

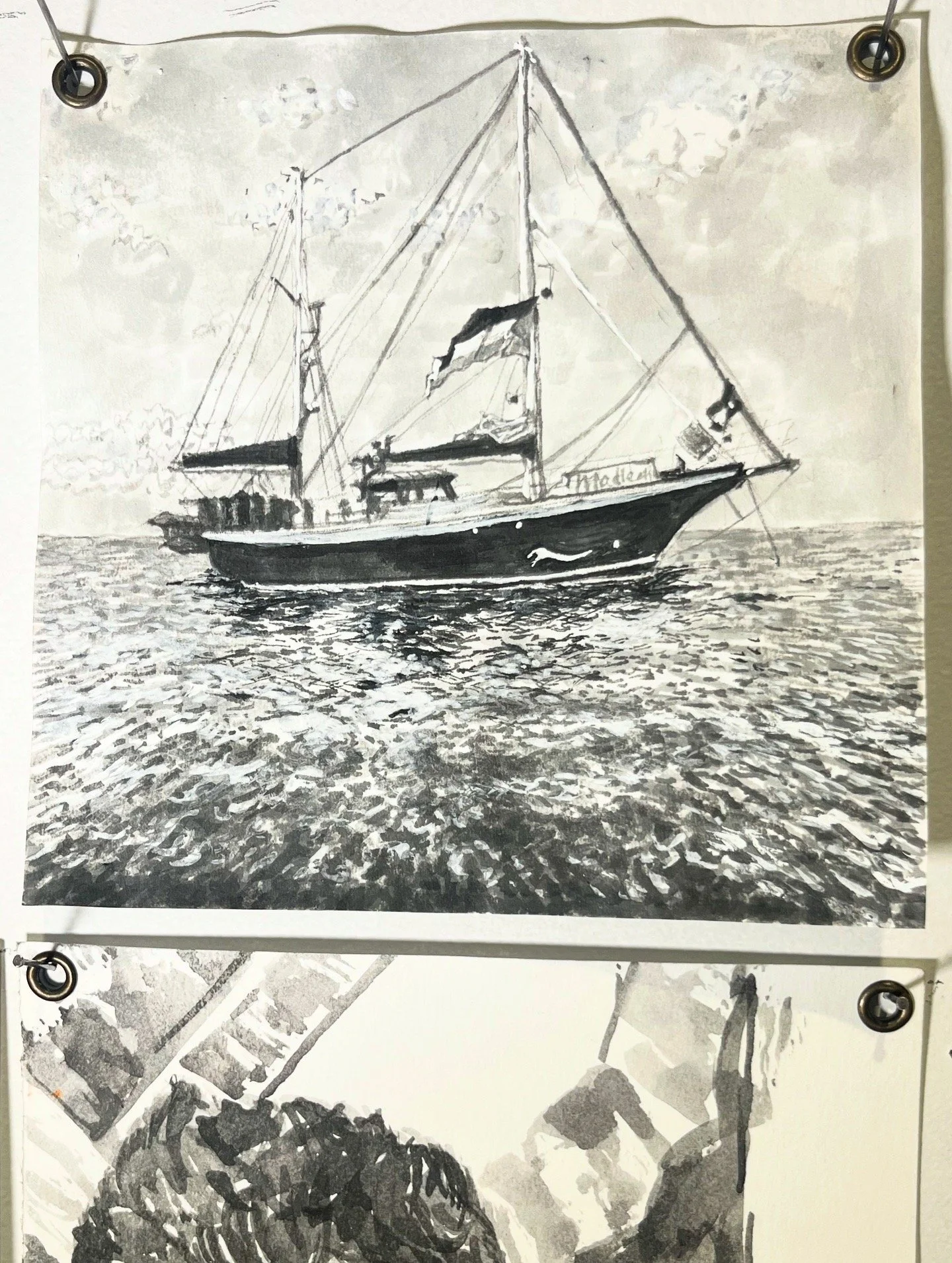

"Artist-Made Shelter for a Man-Made Tragedy Such as Genocide": A large diptych painting doubling as a shelter’s wall within the gallery. Filled with salvaged comforts—family photos, makeshift "windows," a lamp—it asks: Can art offer respite amid relentless violence? The work echoes Palestinian resilience, where beauty persists even in ruins.

Art as Witness, Shelter, and Defiance

Fernández’s practice interrogates art’s role in times of crisis. The shelter installation, though "useless" in practical terms, embodies the I Ching’s Hexagram 22 (Adornment): a tribute to dignity upheld through creativity. Meanwhile, her ink drawings archive collective grief—and the shadow-banning of dissent.

Event Details

Exhibition Dates: 16–22 August 2025

Location: Art Bypass Gallery (We Are Sweet Art Co.), Dalston, London E8

Contact: info@wearesweetart.com

Art Bypass Gallery operates on feminist principles, centring marginalised voices and redefining who creates—and accesses—art.

High-res images & interviews available on request.

ARTIST-MADE SHELTER FOR A MAN-MADE TRAGEDY, SUCH AS GENOCIDE

Accompanying text.

Art is useless. You cannot eat it. You might wear or inhabit it, use it in some practical way—but art does not feed you. And yet, after those who grow our food and those who care for the living, art remains one of humanity’s purest expressions.

Still, in times like these—times of monsters—it feels more useless than ever.

What could I possibly offer those being genocided? Those starved, tortured, bombed relentlessly over rubble, over tents, again and again?

Would I build a shelter? Offer some respite, some beauty, a place to hide—like the forts we made as children under tables, draped in blankets and beach towels?

Would I line it with a mattress, bring my sketchbook and watercolours, a book, a lamp, some water, some sweets?

Or—what would I take if I were the one being erased? My home gone, my belongings scattered, my people slaughtered?

Would I clutch photos of my children, stare at them every day to remember their faces? Would I press my partner’s shirt to my nose, so I don’t forget his scent? Would I salvage a small painting to serve as a window, a few objects to make my shelter feel, even briefly, like a home?

We studied for years so we would never see this happening again. Yet here it is: the same dehumanisation, the same starvation, the same cruelty—only worse. Now, broadcasted on TikTok, proudly tagged, as if genocide were a badge of honour. The weapons are deadlier, the injuries more grotesque. The children, the children of Gaza, that form the largest cohort of amputees in history.

I cannot look away.

I won’t look away.

Because this is bigger than us.

Because, as Omar El Akkad wrote, “One day, everyone will have been against this.” *

I saw an orphaned father hang his children’s toys on a clothesline—all six killed in an airstrike. Would I do the same?

I saw another father stroking his dead boy’s hair the way I stroke my living son’s.

I saw a 12-year-old girl, alone in the world, and thought: She needs a mother. My own daughter was 12 when the genocide began.

I saw an old woman clinging to her husband’s lifeless body after 40 years together. She wouldn’t let go. And I knew—I would feel just as abandoned. All our past fights would vanish in an instant, leaving only the unbearable weight of loss.

Another man lost all four of his children, torn to pieces by Israel. Months later, an orphaned boy called him “baba” without asking permission. Love saved them both. Now, hunger consumes them.

I never knew my knowledge of anatomy could expand so horrifically. I didn’t know bodies could break like this—children shredded, hanging from trees like ribbons. I never imagined people could be pulverised by bombs falling on tents. I never thought I’d see so many small bodies, limp as rag dolls. I didn’t know a body could be crushed so completely that eyes—or fetuses—burst from the pressure.

I also know this: I would not be a perfect victim. Neither would you. I wouldn’t sit quietly, waiting to die. I would resist. Somehow. Survive at any cost.

This is bigger than us.

MY SOCIAL MEDIA FEED ON INK, A SELF PORTRAIT OF A SCROLLING MIND

In a world saturated with digital imagery—where images are endlessly consumed, shared, and forgotten—my work seeks to reclaim the fleeting and the intangible. This ongoing drawing project explores the tension between the digital and the physical, the ephemeral and the permanent. By appropriating compelling images from my social media feed—images that resonate with me on a personal or aesthetic level—I aim to transform them into material objects, grounding them in the tactile reality of paper and ink.

The act of reinterpreting these digital fragments through the slow, deliberate process of drawing is an act of alchemy. It breathes new life into the familiar, turning the mundane into something extraordinary. Each piece becomes a bridge between the virtual and the tangible, inviting viewers to reconsider the nature of perception and the ways we engage with the visual world.

I seek to make these images more real—not in the sense of hyperrealism, but in their ability to evoke a deeper connection and presence. Regarding the images taken from a live-streamed genocide, still ongoing—the cruelest of them all—I seek to make them “unscrollable.” These are real people, not numbers. Names, dreams, aspirations, ambitions, and even the mundane desire for an ordinary, unassuming, normal life.

This is a deliberate alchemy: a slow, meditative process that elevates disposable content into contemplative artifacts.

My Social Media Feed in Ink began during the pandemic as small 13 x 13 cm drawings, growing into an archive of over 200 works, first exhibited in Cartography of Care at Edinburgh’s Spilt Milk Gallery (2022). These pieces form a visual diary that captures the dissonant intimacy of algorithmically curated feeds—where family snapshots coexist with war documentation, and holiday photos brush against consumer advertisements.

The ink becomes both medium and metaphor: a permanent substance fixing transient images, a traditional medium engaging with contemporary visual culture. This practice serves as both resistance to and documentation of our digital consumption patterns, offering viewers space to reconsider how images shape identity, memory, and our understanding of reality.